Minotaur

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Minotaur bust, (National Archaeological Museum of Athens) | |

| Grouping | Mythological creature |

|---|---|

| Parents | Cretan Bull and Pasiphaë |

| Mythology | Greek |

| Region | Crete |

In Greek mythology, the Minotaur (Ancient Greek: Μινώταυρος [miːnɔ̌ːtau̯ros]; in Latin as Minotaurus [miːnoːˈtau̯rʊs]) is a mythical creature portrayed in Classical times with the head and tail of a bull and the body of a man[1] or, as described by Roman poet Ovid, a being "part man and part bull".[2] He dwelt at the center of the Labyrinth, which was an elaborate maze-like construction[3] designed by the architect Daedalus and his son Icarus, on the command of King Minos of Crete. The Minotaur was eventually killed by the Athenian hero Theseus.

Etymology[edit]

The word Minotaur derives from the Ancient Greek Μῑνώταυρος, a compound of the name Μίνως (Minos) and the noun ταύρος "bull", translated as "(the) Bull of Minos". In Crete, the Minotaur was known by the name Asterion,[4] a name shared with Minos' foster-father.[5] In Etruscan, the Minotaur had the name Θevrumineś.

"Minotaur" was originally a proper noun in reference to this mythical figure. The use of "minotaur" as a common noun to refer to members of a generic "species" of bull-headed creatures developed much later, in 20th-century fantasy genre fiction.

English pronunciation of the word "Minotaur" is varied. The following can be found in dictionaries: /ˈmaɪ.nəˌtɔːr, -noʊ-/ MY-nə-tawr, -noh-,[6] /ˈmɪn.əˌtɑːr, ˈmɪn.oʊ-/ MIN-ə-tar, MIN-oh-,[7] /ˈmɪn.əˌtɔːr, ˈmɪn.oʊ-/ MIN-ə-tawr, MIN-oh-.[8]

Creation and appearance[edit]

After ascending the throne of the island of Crete, Minos competed with his brothers as ruler. Minos prayed to the sea god Poseidon to send him a snow-white bull as a sign of the god's favour. Minos was to sacrifice the bull to honor Poseidon, but owing to the bull's beauty he decided instead to keep him. Minos believed that the god would accept a substitute sacrifice. To punish Minos, Poseidon made Minos' wife Pasiphaë fall in love with the bull. Pasiphaë had the craftsman Daedalus fashion a hollow wooden cow, which she climbed into in order to mate with the bull. The monstrous Minotaur was the result.

Pasiphaë nursed the Minotaur but he grew in size and became ferocious. As the unnatural offspring of a woman and a beast, the Minotaur had no natural source of nourishment and thus devoured humans for sustenance. Minos, following advice from the oracle at Delphi, had Daedalus construct a gigantic labyrinth to hold the Minotaur. Its location was near Minos' palace in Knossos.[9]

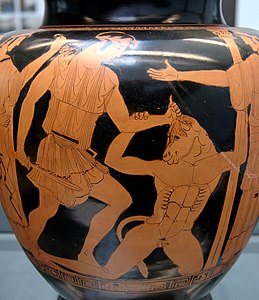

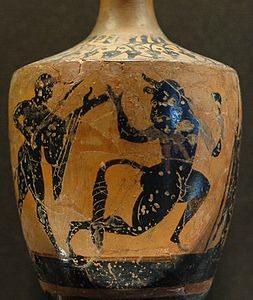

The Minotaur is commonly represented in Classical art with the body of a man and the head and tail of a bull. According to Sophocles' Trachiniai, when the river spirit Achelous seduced Deianira, one of the guises he assumed was a man with the head of a bull.

From Classical times through the Renaissance, the Minotaur appears at the center of many depictions of the Labyrinth.[10] Ovid's Latin account of the Minotaur, which did not describe which half was bull and which half man, was the most widely available during the Middle Ages, and several later versions show a man's head and torso on a bull's body – the reverse of the Classical configuration, reminiscent of a centaur.[11] This alternative tradition survived into the Renaissance, and still figures in some modern depictions, such as Steele Savage's illustrations for Edith Hamilton's Mythology (1942).

Theseus and the Minotaur[edit]

Androgeus, son of Minos, had been killed by the Athenians, who were jealous of the victories he had won at the Panathenaic festival. Others say he was killed at Marathon by the Cretan Bull, his mother's former taurine lover, who Aegeus, king of Athens, had commanded him to slay. The common tradition holds that Minos waged and won a war to avenge the death of his son. Catullus, in his account of the Minotaur's birth,[12] refers to another version in which Athens was "compelled by the cruel plague to pay penalties for the killing of Androgeos." Aegeus had to avert the plague caused by his crime by sending "young men at the same time as the best of unwed girls as a feast" to the Minotaur. Minos required that seven Athenian youths and seven maidens, drawn by lots, be sent every seventh or ninth year (some accounts say every year[13]) to be devoured by the Minotaur.

When the third sacrifice approached, Theseus volunteered to slay the monster. He promised his father, Aegeus, that he would put up a white sail on his journey back home if he was successful, but would have the crew put up black sails if he was killed. In Crete, Minos' daughter Ariadne fell madly in love with Theseus and helped him navigate the labyrinth. In most accounts she gave him a ball of thread, allowing him to retrace his path. Theseus killed the Minotaur with the sword of Aegeus and led the other Athenians back out of the labyrinth.[citation needed] On the way home, Theseus abandoned Ariadne on the island of Naxos and continued. He neglected, however, to put up the white sail. King Aegeus, from his lookout on Cape Sounion, saw the black-sailed ship approach and, presuming his son dead, committed suicide by throwing himself into the sea that is since named after him.[14] This act secured the throne for Theseus.

Etruscan view[edit]

The view of the Minotaur as the antagonist of Theseus reflects the literary sources, which are biased in favour of the Athenian perspectives. The Etruscans, who paired Ariadne with Dionysus, never with Theseus, offered an alternative view, never seen in Greek arts: on an Etruscan red-figure wine-cup of the early-to-mid fourth century Pasiphaë tenderly cradles an infant Minotaur on her knee.[15]

Interpretations[edit]

The contest between Theseus and the Minotaur was frequently represented in Greek art. A Knossian didrachm exhibits on one side the labyrinth, on the other the Minotaur surrounded by a semicircle of small balls, probably intended for stars; one of the monster's names was Asterion ("star").

While the ruins of Minos' palace at Knossos were discovered, the labyrinth never was. The multiplicity of rooms, staircases and corridors in the palace has led some archaeologists to suggest that the palace itself was the source of the labyrinth myth, an idea that is now generally discredited.[16] Homer, describing the shield of Achilles, remarked that Daedalus had constructed a ceremonial dancing ground for Ariadne, but does not associate this with the term labyrinth.

Some modern mythologists regard the Minotaur as a solar personification and a Minoan adaptation of the Baal-Moloch of the Phoenicians. The slaying of the Minotaur by Theseus in that case indicates the breaking of Athenian tributary relations with Minoan Crete.[17]

According to A. B. Cook, Minos and Minotaur were different forms of the same personage, representing the sun-god of the Cretans, who depicted the sun as a bull. He and J. G. Frazer both explain Pasiphaë's union with the bull as a sacred ceremony, at which the queen of Knossos was wedded to a bull-formed god, just as the wife of the Tyrant in Athens was wedded to Dionysus. E. Pottier, who does not dispute the historical personality of Minos, in view of the story of Phalaris, considers it probable that in Crete (where a bull cult may have existed by the side of that of the labrys) victims were tortured by being shut up in the belly of a red-hot brazen bull. The story of Talos, the Cretan man of brass, who heated himself red-hot and clasped strangers in his embrace as soon as they landed on the island, is probably of similar origin.

A historical explanation of the myth refers to the time when Crete was the main political and cultural potency in the Aegean Sea. As the fledgling Athens (and probably other continental Greek cities) was under tribute to Crete, it can be assumed that such tribute included young men and women for sacrifice. This ceremony was performed by a priest disguised with a bull head or mask, thus explaining the imagery of the Minotaur.

Once continental Greece was free from Crete's dominance, the myth of the Minotaur worked to distance the forming religious consciousness of the Hellene poleis from Minoan beliefs.

A scientific interpretation also exists. Citing early descriptions of the minotaur by Callimachus as being entirely focused on the "cruel bellowing" it made from its underground labyrinth and the extensive tectonic activity in the region, science journalist Matt Kaplan has theorised that the myth may well stem from geology. [19] He points out that carbon dating of marine fossils attached to boulders that were ejected from the ocean by ancient tsunamis indicates the region was tectonically very active during the years when the minotaur myth first appeared.[20] Given this, he argues that the Minoans used the monster to help explain the terrifying earthquakes that were "bellowing" beneath their feet.

Cultural references[edit]

This section appears to contain trivial, minor, or unrelated references to popular culture. (May 2020) |

Dante's Inferno[edit]

The Minotaur (infamia di Creti, Italian for "infamy of Crete"), appears briefly in Dante's Inferno, in Canto 12 (l. 12–13, 16–21), where Dante and his guide Virgil find themselves picking their way among boulders dislodged on the slope and preparing to enter into the seventh circle of hell.[21]

Dante and Virgil encounter the beast first among the "men of blood": those damned for their violent natures. Some commentators believe that Dante, in a reversal of classical tradition, bestowed the beast with a man's head upon a bull's body,[22] though this representation had already appeared in the Middle Ages.[23]

|

|

In these lines, Virgil taunts the Minotaur in order to distract him, and reminds the Minotaur that he was killed by Theseus the Duke of Athens with the help of the monster's half-sister Ariadne. The Minotaur is the first infernal guardian whom Virgil and Dante encounter within the walls of Dis.[24] The Minotaur seems to represent the entire zone of Violence, much as Geryon represents Fraud in Canto XVI, and serves a similar role as gatekeeper for the entire seventh Circle.[25]

Giovanni Boccaccio writes of the Minotaur in his literary commentary of the Commedia: "When he had grown up and become a most ferocious animal, and of incredible strength, they tell that Minos had him shut up in a prison called the labyrinth, and that he had sent to him there all those whom he wanted to die a cruel death".[26] Dante Gabriel Rossetti, in his own commentary,[27][28] compares the Minotaur with all three sins of violence within the seventh circle: "The Minotaur, who is situated at the rim of the tripartite circle, fed, according to the poem was biting himself (violence against oneself) and was conceived in the 'false cow' (violence against nature, daughter of God)."

Virgil and Dante then pass quickly by to the centaurs (Nessus, Chiron, Pholus, and Nessus) who guard the Flegetonte ("river of blood"), to continue through the seventh Circle.[29]

Surrealist art[edit]

- From 1933 to 1939, Albert Skira published an avant-garde literary magazine Minotaure, with covers featuring a Minotaur theme. The first issue had cover art by Pablo Picasso. Later covers included work by Salvador Dali, Rene Magritte, Max Ernst, and Diego Rivera.

- Pablo Picasso made a series of etchings in the Vollard Suite showing the Minotaur being tormented, possibly inspired also by Spanish bullfighting.[30] He also depicted a Minotaur in his 1933 etching Minotaur Kneeling over Sleeping Girl and in his 1935 etching Minotauromachy.

- The Minotaur appears as the protagonist of Steven Sherill's The Minotaur Takes a Cigarette Break.[31] The character returns in The Minotaur Takes His Own Sweet Time.[32]

Other derivative works and cultural references[edit]

- The short story The House of Asterion by the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges gives the Minotaur's story from the monster's perspective.

- The documentary Room 237 suggests that the film The Shining (1980) is a re-telling of the myth of the Minotaur.

- A minotaur, descended from the original mythological figure, appears in the third episode of the 2014 television series The Librarians ("And The Horns of a Dilemma"). Golden Axe Foods, an agribusiness firm founded by survivors of the Minoan civilization (the name refers to a symbol of the Minoan monarchy), have imprisoned the minotaur to recreate the Labyrinth in order to maintain their wealth and prosperity. The minotaur is presented as a large, bull-headed man in leather garb, who can shapeshift into the form of a muscular biker. It is freed when the labyrinth is destroyed, and proceeds to exact revenge upon its captors.

- A minotaur named Iron Will is a supporting character in My Little Pony Friendship is Magic.

- In the Gargoyles (episode "The New Olympians"), a minotaur named Taurus is a New Olympian after the father was killed by Proteus and serves as a false antagonist.

- In the animated TV series Aladdin, a huge minotaur named Dominus Tusk was killed by the Sultan and had his horns mounted as a trophy.

- In the Doctor Who episode "The Time Monster", set in Bronze Age Thera, the Minotaur appears played by Dave Prowse.

- In the Legend of the Three Caballeros (episode "Labyrinth and Repeat"), the Minotaur chases Donald Duck, José Carioca and Panchito Pistoles in the hidden labyrinth but dies crushed under a pile of rocks.

- In Jake and the Never Land Pirates a minotaur named Monty appears in two episodes ("Minotaur Mix-Up") and ("Captain Buzzard to the Rescue!") as a guardian of the treasure of Argos Island. Unlike his Greek mythological counterpart, he is depicted as friendly.

- The Minotaur appears in the first book in the Percy Jackson & the Olympians series, The Lightning Thief (2005), where he battles and is killed by Percy Jackson. He is reborn and reappears in the fifth book, The Last Olympian (2009).

- In the Doctor Who episode "The God Complex", the Doctor, Amy and Rory find themselves in a mysterious hotel with rooms and corridors that constantly change to form an endless labyrinth, allowing the minotaur trapped inside to hunt people down one by one with their secret fears until they give in and are consumed.

- Mark Z. Danielewski's novel House of Leaves features both the labyrinth and the Minotaur as prominent themes.

- In the Brazilian telenovela Os Mutantes: Caminhos do Coração, a man is transformed into the Minotaur and placed on an island with several other mutants.

- The titular kaiju of Pulgasari has the appearance of a minotaur, and is based on the metal-eating folk monster Bulgasari.

- Aleksey Ryabinin's book Theseus (2018).[33][34] provides a retelling of the myths of Theseus, Minotaur, Ariadne and other personages of Greek mythology.

- The Minotaur, an opera by Harrison Birtwistle.

- Minotauria is a genus of Balkan woodlouse hunting spiders named in its honor.[35]

- The Netflix TV series Dark alludes to the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur in a number of episodes, and part of the series' story involves navigating labyrinthian underground tunnels.

Board and video games[edit]

- The popular role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons features Minotaurs.[36]

- Madness and the Minotaur is a 1981 text adventure game for the TRS-80 Color Computer[37]

- The storyline of the 2017 virtual reality video game Theseus revolves around the titular hero's mission to defeat the Minotaur.[38]

- In the mobile game Fate/Grand Order, the Minotaur, named Asterios in the game, is one of the Servants that can be summoned by the player. Asterios is a Berserker-class Servant, and pretty close with Euryale, one of the Gorgon sisters.

- In Assassin's Creed: Odyssey (2018), there is a mission where the main character (Alexios or Kassandra) visits the ruins of the Palace of Knossos in order to kill the Minotaur in the Labyrinth of the Lost Souls.[39]

- In the video game Hades (2019) by Supergiant Games, the protagonist defeats the Minotaur (named Asterius) in Elysium, where he fights beside Theseus.[40]

Film[edit]

- Minotaur, the Wild Beast of Crete is a 1960 Italian film. The film was directed by Silvio Amadio and starred Bob Mathias.[41]

- Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger was directed by Sam Wanamaker. Peter Mayhew played the Minotaur is his first role in 1976.[42][43]

- Minotaur, a horror adaption of the legend, was released on DVD by Lions Gate on June 20, 2006. Maple Pictures would also release the film in Canada that same day. It was later released by Brightspark on September 3, 2007.[44]

- Sinbad and the Minotaur is a film released in 2011, directed by Karl Zwicky.[45]

- Wrath of the Titans, a sequel to the 2010 film Clash of the Titans and directed by Louis Leterrier.

See also[edit]

This "see also" section may contain an excessive number of suggestions. Please ensure that only the most relevant links are given, that they are not red links, and that any links are not already in this article. (May 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

- Bull-Leaping Fresco, Minoan Bull-leaper - Minoan era depictions of bull-leaping

- Centaur - a legendary human-horse hybrid

- Comparable entities

- Apis – an Egyptian god depicted as a bull or bull-headed man

- Mahishasura – a buffalo-headed Asura

- Moloch (or Ba'al) – a god worshipped in the Middle East depicted as a horned man

- Nandi – a bull who serves Lord Shiva in Hindu mythology

- Ox-Head – guardian of the Underworld in Chinese mythology, who has a bull's head and a human body

- Sarangay – a creature resembling a bull with a huge muscular body and a jewel attached to its ears

- Shedu – a figure in Mesopotamian mythology with the body of a bull and a human head

- Ushi-oni – a bull-headed monster from Japanese folklore

References[edit]

- ^ Kern, Hermann (2000). Through the Labyrinth. Munich, London, New York: Prestel. p. 34. ISBN 3791321447.

- ^ semibovemque virum semivirumque bovem, according to Ovid, Ars Amatoria 2.24, one of the three lines that his friends would have deleted from his work, and one of the three that he, selecting independently, would preserve at all cost, in the apocryphal anecdote told by Albinovanus Pedo. (noted by J. S. Rusten, "Ovid, Empedocles and the Minotaur" The American Journal of Philology 103.3 (Autumn 1982, pp. 332-333) p. 332.

- ^ In a counter-intuitive cultural development going back at least to Cretan coins of the 4th century BC, many visual patterns representing the Labyrinth do not have dead ends like a maze; instead, a single path winds to the center. See Kern, Through the Labyrinth, Prestel, 2000, Chapter 1, and Doob, The Idea of the Labyrinth, Cornell University Press, 1990, Chapter 2.

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece 2. 31. 1

- ^ The Hesiodic Catalogue of Women fr. 140, says of Zeus' establishment of Europa in Crete: "...he made her live with Asterion the king of the Cretans. There she conceived and bore three sons, Minos, Sarpedon and Rhadamanthys."

- ^ "English Dictionary: Definition of Minotaur". Collins. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ^ [1][2][3]

- ^ "American English Dictionary: Definition of Minotaur". Collins. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Several examples are shown in Kern, Through the Labyrinth, Prestel, 2000.

- ^ Examples include illustrations 204, 237, 238, and 371 in Kern. op. cit.

- ^ Carmen 64.

- ^ Servius on Aeneid, 6. 14: singulis quibusque annis "every one year". The annual period is given by J. E. Zimmerman, Dictionary of Classical Mythology, Harper & Row, 1964, article "Androgeus"; and H. J. Rose, A Handbook of Greek Mythology, Dutton, 1959, p. 265. Zimmerman cites Virgil, Apollodorus, and Pausanias. The nine-year period appears in Plutarch and Ovid.

- ^ Plutarch, Theseus, 15—19; Diodorus Siculus i. I6, iv. 61; Bibliotheke iii. 1,15

- ^ The wine cup is illustrated in Larissa Bonfante and Judith Swaddling, Etruscan Mythology (Series The Legendary Past, British Museum / University of Texas at Austin) 2006, fig.29 p. 44 ("early fourth century") (on-line illustration).

- ^ Sir Arthur Evans, the first of many archaeologists who have worked at Knossos, is often given credit for this idea, but he did not believe it; see David McCullough, The Unending Mystery, Pantheon, 2004, p. 34-36. Modern scholarship generally discounts the idea; see Kern, Through the Labyrinth, Prestel, 2000, p. 42-43, and Doob, The Idea of the Labyrinth, Cornell University Press, p. 1990, p. 25.

- ^ The Encyclopaedia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information. Encyclopaedia Britannica Company. 1911.

- ^ Paolo Alessandro Maffei, Gemmae Antiche, 1709, Pt. IV, pl. 31; Hermann Kern, Through the Labyrinth, Prestel, 2000, fig. 371, p. 202): Maffei "erroneously deemed the piece to be from Classical antiquity".

- ^ Callimachus first refers to the minotaur with the phrase "Having escaped the cruel bellowing and the wild son of Pasiphaë and the coiled habitation of the crooked labyrinth"; see "Callimachus, Hymns and Epigrams." Translated by A. W. Mair and G. R. Mair. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1921. Kaplan argues that the minotaur is the result of ancient people trying to explain earthquakes;see Kaplan, Matt, "Science of Monsters, New York, NY, Simon and Schuster, 2012

- ^ see Scheffers, Anja, et al. “Late Holocene Tsunami Traces on the Western and Southern Coastlines of the Peloponnesus (Greece).” Earth and Planetary Science Letters 269 (2008): 271–79

- ^ The traverse of this circle is a long one, filling Cantos 12 to 17.

- ^ Inferno XII, Verse Translation by Dr. R. Hollander, p. 228 commentary

- ^ Kern, Hermann (2000). Through the Labyrinth. Munich, London, New York: Prestel. p. 116–117. ISBN 3791321447.

- ^ The fallen angels, the Erinyes [Furies], and the unseen Medusa were located on the city's defensive ramparts in Canto IX.

- ^ Boccaccio Comedia delle ninfe fiorentine commentary

- ^ Boccaccio's Expositions on Dante's Comedy, University of Toronto Press, 30 Nov 2009

- ^ Bennett, Pre-Raphaelite Circle, 177-180.

- ^ "Dante Family letters Rossetti Archive". Rossettiarchive.org.

- ^ Beck, Christopher, "Justice among the Centaurs," Forum Italcium 18 (1984): 217-29

- ^ Tidworth, Simon Theseus in the Modern World essay in The Quest for Theseus London 1970 pp244-9 ISBN 0269026576

- ^ O'Grady, Megan (12 December 2002). "Dreaming of Hoofbeats". The New York Times.

- ^ Gurganus, Allan (2 October 2016). "A Minotaur's in Maintenance in a Tale of Rust Belt America". The New York Times.

- ^ A.Ryabinin. Theseus. The story of ancient gods, goddesses, kings and warriors. – СПб.: Антология, 2018. ISBN 978-5-6040037-6-3.

- ^ O.Zdanov. Life and adventures of Theseus. // «KP», 14.02.2018.

- ^ Kulczyński, W. (1903). "Aranearum et Opilionum species in insula Creta a comite Dre Carolo Attems collectae". Bulletin International de l'Academie des Sciences de Cracovie. 1903: 32–58.

- ^ DeVarque, Aardy. "Literary Sources of D&D". Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ "Madness and the Minotaur (1982)". Dragon Data. 1982. p. 3. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- ^ "Theseus on the PlayStation Store". Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ Billcliffe, James (1 November 2018). "Assassin's Creed Odyssey A Place of Twists and Turns Quest Guide – How to find and defeat the Minotaur to get the artifact". vg247. Gamer Network. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- ^ "HADES: Get Pumped for 'The Beefy Update'!". www.epicgames.com. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- ^ "The Minotaur, the Wild Beast of Crete". Letter Box. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ Hutchinson, Sean (19 May 2015). "15 Chewbacca Facts in Honour of Peter Mayhew's Birthday". Mental Floss. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ^ "Peter Mayhew, Chewbacca in 'Star Wars' franchise, dies at 74". NBC News. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ "Minotaur (2005) - Jonathan English". Allmovie.com. AllMovie. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ Foywonder (21 March 2011). "Sinbad and the Minotaur (2011)". Dread Central. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

External links[edit]

- Minotaur in Greek Myth source Greek texts and art.